In retrospect: Journey Mapping is such a great exercise to help teams understand their true users and what they struggle with. I have run this activity many times with participants ranging from retail executives and store associates to university students. This blog outlines a journey mapping session I ran when I was heading up product at Tulip Retail (a startup focussed on mobile applications for store associates). There are always user insights that come out of this activity. It also makes end user points of friction within a process very clear which you can then use as a basis to solution on (and not always with software even!). I also used this blog post as the basis for a talk I gave at the Grace Hopper conference in Austin in 2018. I will share my application and presentation in a future post.

ORIGINAL POST FOLLOWS FROM DECEMBER 18, 2017

(https://medium.com/@sarah.mcmullin_82646/returns-the-problem-that-keeps-coming-back-8e45dcbb7a37)

A friend passed me a tweet story entitled “Things Many People Find Too Obvious to Have Told You Already”, in which the author outlined many known knowns about start-ups. I would propose there is something inherently valuable about communicating known knowns. Why? Simply more often than not known knowns are not all known, and important nuances are suddenly made more apparent after their communication (like in this tweet story). To further this premise, I would like to use a recent Design Thinking exercise around journey mapping we ran at Tulip that illustrates the value of communicating these known knowns.

But first a bit about Empathy

At the heart of Design Thinking is empathy — truly understanding the person you are designing a solution for (your user). It’s honestly one of the hardest things I think for some to grasp, because like many, we feel like we know the user already. Anyone working within product has seen software feature requests that have clearly exhibited lack of empathy for a user. Maybe it was something that made life easier for IT, or it was a great idea put forward by an executive. But for the user, it neither addressed a pain nor provided delight. Often in these circumstances the user was thought to already be understood, or worse the user was never thought about at all. These known knowns are proven to be unknown.

It is easy to fall into the substitute user framework. Imagine my predicament when I am asked to design something for a store associate? I know retail right. I mean, I do LOVE to shop. Surely I can create software that fulfils store associate needs? This is where a simple tool like journey mapping can help.

And a bit about Journey Mapping

A journey map is a visual way to tell a story. A story is a great framework because its elements help to set up reasonable constraints. For example, a story has a timeline: a beginning, middle, and an end, which can further be divided into stages. A story also has characters that interact with the story teller. Lastly, a story has plot devices like conflict.

Similarly, journey mapping produces a visual summary of all the actions a user takes, all the touchpoints (interactions with people, places, things/tech) that were made, and all the points of friction encountered along the way. A journey map results in a visual summary that communicates user empathy to dispel any misconceptions around the known knowns of the user.

Tell us your story of the last major purchase you made: how we ran this at Tulip

At Tulip we chose not to assume anything about our users, so we invited retailers and shoppers to come to a Design Thinking session focussed exclusively on journey mapping. We split the retailers and store associates into two groups and through a series of exercises had them tell their stories. The retailers told stories of how they helped customers make a major purchase and the shoppers told stories of a recent major purchase they had. We then invited the groups to highlight any touchpoints (persons/places/things/tech) that they interacted with throughout their journey, creating and labelling the stages in their journey along the way. Finally we had the teams overlay feelings throughout the journey with emojis.

Here is a visual of the end result:

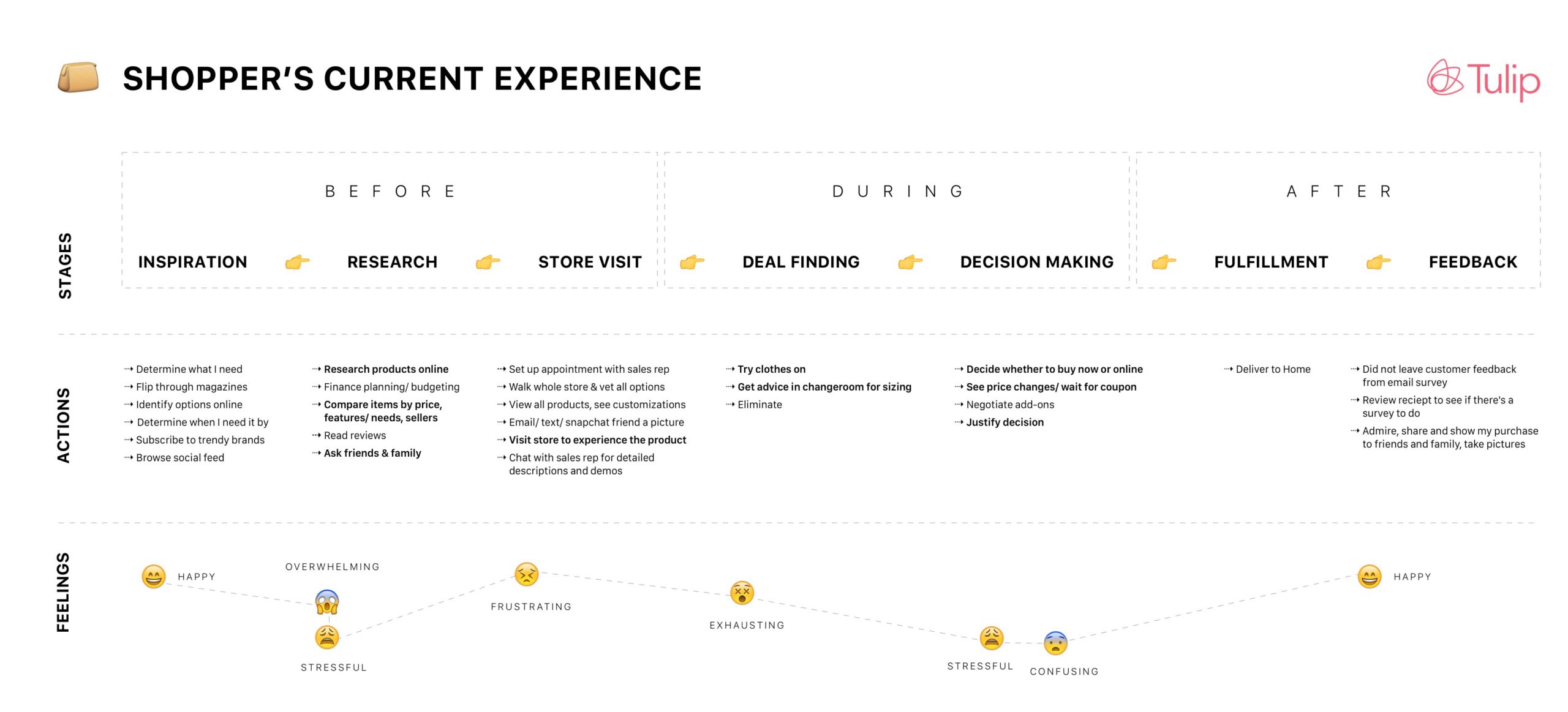

And here is the final aggregated journey map of today’s shopper:

Shopper Known Knowns

So as a shopper myself, I still learned more about shoppers through this journey mapping exercise than I knew before.For example, I was surprised at how much time other shoppers spend on finding deals, and the roller coaster of emotions associated with finding deals pre-and-post purchase. Another interesting insight was the strong desire shoppers have to experience products in real life which ultimately drove them to the store to begin with (even if later they went home to buy that product online). Clearly communicating known knowns has its merits in aligning common understanding around a user.

Ultimately though, communicating real known knowns around users leads to defining the real problems to solve. Using our previous example, we may want to look at solving alleviating deal finding fatigue, or enhancing the in-store experience to make it even more real. All examples of real innovation sparked by known knowns and Design Thinking in action.